(STARS) Strange attractors in the collection

…

Is everybody in?

Is everybody in?

Is everybody in?

The ceremony is about to begin

…

“Celebration of the Lizard” was a Doors composition “pieced together…out of already existing elements” that was performed at various live concerts of the band before it made its official recorded debut on their 1970 live album, Absolutely Live. Jim Morrison’s cry during those live shows is what triggered and named this project, because of how it echoed and resonated, from the wild ’60s all the way to the 2020s pandemic lockdown.

The collective crossing that cry was chanting feels like a most urgent question at the current disorienting moment where the world seems to be in a state of long Covid; a state of fatigue, indifference, low-boiling anger, distrust towards science, fear visàvis a faceless future, if not a right-out global meltdown. A moment when solidarity, communication, reality, are things shattered and assembled anew according to the power and malevolence of disparate agencies.

“We are living through a long anti-1960s,” writes Simon Critchley in “Mystical Anarchism.” “We now know better than to try to bring heaven crashing down to earth and construct concrete Utopias. To that extent, despite our occasional and transient enthusiasms, we are all political realists; indeed most of us are passive nihilists and cynics…Perhaps such utopian experiments in community only live on in the institutionally sanctioned spaces of the contemporary art world.” Critchley’s critique of the existence of a certain “mannerist Situationism” could be justified. The co-optation and void reenactment of avant-garde tactics by the art establishment and related market is evident and pervasive. Yet there are still other ways that go beyond the relational spectacles of inclusion, which perpetuate existing systems of status distribution; ways that practice “the politics of love” for which the philosopher yearns; ways that confront the regulative response enforced by neoliberal governance visàvis the radical insurgency of the ’60s.

Think expressions of solidarity, joyful militancy and pleasure activism; think insurgent sociocultural entanglements and speculative, transdisciplinary, intersectional alliances of degrowth, convivial tools and slapstick humor tactics; think heterodox post-growth approaches, artistic research formats of “resisting and insisting,” mutual aid ecosocial practices, queer/radical futurisms; think feral energies that stem from traditions of the oppressed and indigenous knowledges, critical reassessments of suppressed histories and neglected archives; think even new forms of refusal, movements of desertion from the grip of integrated world capitalism and digital information technology, that may give birth to new solidarities. Think with, as in do with, paradoxes and pluriversal cosmopolitics where many worlds fit despite their uncommoning.

Think with the words of Saidiya Hartman’s engagement with black social life that has been unthought for very long; her attentiveness to everyday gestures of radical living, which, at the beginning of the 20th c., formed the ground of insurgency where assembling, rebellion and wild imagination still grow today.

Think with Fred Moten and Stefano Harney who, assuming the role of the griot, revisit Pasolini’s prophesy of a rioting blackness and call upon “Ali Blues Eyes,” the plural leader of “a holy river come down procession” that cannot teach, but can only be joined “when one comes up from under and falls back into its surf,” when one steps into the study, into the jam, into deferred dreams that create sociality.

Think with Denise Ferreira da Silva’s anticolonial black feminist poethics and her take on tenderness, the nonlinear, inseparability, quantum solidarity.

Think with the work of scholars and curators who challenge modern and present framings of global disaster, climate catastrophe and societal injustice, and address current disciplinary enclosures, new chronopolitics, the intertwining of art and social fights, the potential of new toolboxes for the liberation of imaginaries, the work that needs to be done in the fields of life.

Think with Jack Halberstam’s fascinating take on aesthetics of collapse and bewilderment, “silly archives,” the disorder of desire and wildness.

Think with Andreas Malm’s emerging forms of sabotage, and expressions of civil disobedience (Extinction Rebellion, the Last Generation group, Liberate Tate, Institute of Radical Imagination, Anarchists Against the Wall, The Red Nation, Not An Alternative, Colectiva Feminista en Construcción, and many others), visàvis the escalating violence of racial Capitalocene; ceremonies of anti-authoritarianism that reshape current sociocultural landscapes and translate traditions of eco-anarchism, indigenous land-based struggles, and philosophical decolonial worldviews (like those of Frantz Fanon, Sylvia Wynter, Édouard Glissant, and more).

Think with Judith Butler’s understanding of anarchism as a noncontinuous movement, rather than an identity; a form of peaceful thinking-in-action that can interrupt and confuse consolidated forms of state power and restrictive norms in various sociocultural fields.

Think with David Graeber’s radical and incisive take on the future of economy, debt, and the injustices built in social relationships and bureaucratic technologies; with Michael Taussig’s ecopoetic, apotropaic writing on the Mastery of Non-Mastery in the Age of Meltdown, a “book of traces and tremors” that entangles analysis with its object in order to challenge the authorial, extractivist violence of ethnographic study, hegemonic knowledge building and exploitation of nature. Taussig calls forth the magic of multispecies communication, a reinvigorated use of mimesis and the chaos of weather moves in order to visit the point where “the meltdown of the language of nature swamps the nature of language.” His storytelling on “the resistance of fireflies” is a most inspiring appeal to the force of nonviolence, its time and history.

Donna Haraway had best anticipated the viral apocalypse that humanity is now facing and suggested that we stay with the trouble as critters, in sympoietic hope, odd kinships, interlaced trails and string figures, careful to avoid the delusion of techno-totalitarianism.

Franco “Bifo” Berardi recalled it all in 2020, starting from the way Burroughs spoke of viruses as agents of mutations; “The year 2020 should be seen as the year when human history dissolved,” he ceremoniously announced, saluted the return of “usefulness” and called for the political empowerment of solidarity, scientific intelligence, pleasure in conjunction via—among other things—the reassessment of former movements of radical inquiry and their creative insurgency tactics.

That was about the time that this exhibition emerged during the first lockdown experience.

In that atmosphere of growing alienation, lack and estrangement, we sheltered separately, “but together, and not in place, but on the move,” recalling Moten and Harney’s conversation—“When We Are Apart We Are Not Alone”—about the meaning of a blurred and “irreducible sociality of the senses”; we considered the urgency of revolt against individuation and sovereignty, the joy of solidarities, “the groove and swing” that communities share and assemblies invoke. We considered what Zun Lee has described as “possibilities for presencing in and through experimentation”, the fascinating notion of “un-com-prehensible incompleteness” that, as per Denise Ferreira da Silva, “signals how all that exists has as missing that part through which each and everything exists with/as/in something else.”

Our group’s virtual detour inside the ACG Art Collection was a mediated trip into a place of incompleteness that reflects ceremonies of gifting rather than strategic acquisitions and rigorous classifications; a virtual visit to a secluded, temporarily quarantined, inaccessible planet, from where artists, works, things, stories called to this exhibition as they were being called by it. This was not the straight-line kind of visit that every other such exhibition project was able to follow. It was not even a curve. It was rather a kink, or even the collection of kinks, the collective of kinks that Denise Ferreira da Silva recognized in the dread, the jam.

Denied firsthand experience and scrutiny—the holy grail of every archival hunt—this trip took on the character of a jam, an improvisational play-chasing with ghosts, or faraway stars, rather than a gaze upon trophies, relics, possessions. The works were thus approached in a flow that wonders throughout exhibition and notebook; they were saluted as displaced storytellers, agitators and agents that could bind different times in unforeseen ways, summon us into a different kind of study that is work toward incompletion, diffunity.

This notebook chooses to linger here in the rub, the “hapticality”—to borrow Moten’s vibrant term—between the works of Liliane Lijn, Michael Lekakis and Nikos Velmos. Works which, different though they may be in scale, history and circumstance, brush up against one another and share a certain feel that goes beyond comparative intentions and elective affinities; works that have grown in under/over-theorized grounds and have eluded the sustained attention and sanctioning of institutional channels; that have ventured beyond the confines of aesthetics and refused disciplinarian structures (linguistic, formal, cultural); that entertain a certain kind of untimeliness and transmit the wish for an osmotic relationship with the world; works that involve notebooks, works that inhabit crossroads.

Liliane Lijn (1939–)

Lijn’s “Crossing Map” is an artist’s book that marks a special moment of empowerment in the artist’s evolution, reflecting her deep engagement with nuclear physics, astronomy and light as a medium, and ultimately serving as a conduit in her quest for freedom, for her own “road to pleasure.”

Initiated at the time that the mesmerizing, pregnant with discoveries, installation “Liquid Reflections” (1968, also at the ACG Art Collection) was presented at the Indica Gallery in London, “Crossing Map” sprang from a dream as per Lijn’s own account.

“I woke up suddenly. A dense feeling as if my head glowed with light. The heat moving through my mouth and between my lips…I was pure light…No more problems of how to get there—anywhere. Matter was no longer an obstacle.”

It developed as a notebook (with the heading “Atom-Man Notes – Dream fails to jump time gap”), as a sci-fi novel (titled “Time Zone”) and, in 1983, took the form of a storied visual score, a web of drawings and words that pulls together quantum physics, dreamscapes, random newspaper discoveries, charts of personal events, cosmic occurrences, scientific findings, surrealist bewildering ruminations as in André Breton’s “Nadja” where imprévu and déjà vu, the fortuitous and the foreordained, were confronted as aspects of the most enigmatic concept of “objective chance.” This visionary reflection on the dematerialization of man, on the nature of time and the flow of energy, is a form of SF that celebrates the collective mind in a grand gesture of exteriorization. It is a ceremony of self-discovery that develops into a space-time map of crossings and entanglements, haunted by a serial repetition of unique encounters, meant to be read aloud, “perhaps with a friend” as per the artist’s suggestion.

Lijn considered “Crossing Map” her “credo as a woman” and engaged in fascinating public readings which activated it into a feminist manifesto, a cry of joyful mourning for what is and what could be, a challenge to representation, a way “to demolish the barrier between the observer and the observed.”

[Image on the left: Liliane Lijn performing ‘Crossing Map’ poems, Roundhouse London, 1980]

[Image on the right: ‘Crossing Map’ book cover and the diagram that inspired it

The book’s unpunctuated blend of words and drawings (letters, dots, lines, marks pentagrams, nets, vortexes, trigrams, etc.), its ”songs” (in lieu of chapters), are a riotous dance of speculative fabulation, rooted in the artist’s love for surrealist works, scientific diagrams, Buddhist philosophy, cosmic forms, alchemical unions, laws of physics, moving shapes. Words and patterns take flight like some kind of murmuration (the swooping and swirling of starlings) spread across the book’s pages. In a way, this move precipitates recent pieces like her “Gravity’s Dance” (2019), a huge swirling dark skirt with edges of light. The relationship between small marks, their slight shift, creates patterns, and Lijn explores the idiorrythmies at play.

The cover image and title of “Crossing Map” take after a diagram that she had seen in 1973, during a presentation about high-energy (particle) physics, a behavior of matter that, she thought, could be applied to the realm of human relations. Dis/re/assembled in the book’s end, this shape reveals its vaginal undertone, a clear nod to a body giving birth (her body), becoming another, in the crossing lines of infinite encounters and space-time travelling.

And their meetings were many and strong

The many lines crossed between them

Forming the everchanging weave

Of the tribeless tribe

The ultimate family

To meet this work in the present moment is to grasp the transagency of a pioneering feminine gesture that addresses the cosmos diving in and out of the self, facing up to man “the energy addict,” welcoming the pluriversality of being.

Ursula Le Guin’s wandering pacifist anarchism in “The Dispossessed” (1974) comes to mind, as well as Karen Barad’s “TransMaterialities: Trans*/Matter/Realities and Queer Political Imaginings“; in the latter, the zig-zagged musings of lightning become a map for “reaching toward,” for creating new political imaginaries “with material existences in the thick now of the present,” superpositions of many beings, times and “charged yearnings,” “im/possibilities that coexist and are iteratively intra-actively reconfigured.”

The night I dreamt I vomited light is the last verse of song 10, “The Dream,” in Lijn’s work. In it she undergoes a metamorphosis, with a dream as a conduit, much like in the beginning of this artist’s book.

It is also the verse that The Callas embraced in making their own work for “is everybody in? the ceremony is about to begin.”

This is indeed a crossing among many others, an encounter that echoes Liliane Lijn’s autobiographical account of art making: “my work is a coming together of the many secret facets of what I am which is not me.”

Michael Lekakis (1907–1987)

[Image on the left: Michael Lekakis in his studio, photo by Willa Percival, from the catalogue ‘Michael Lekakis, A Retrospective Exhibition’, March, 1987, Kouros Gallery, NY, USA, p. 4]

[Image on the right: The tools of Michael Lekakis (ca 1945-1987) , from The American College of Greece Art Collection, gift of Takis Efstathiou]

A Greek immigrant’s flower shop immersed in the everyday life of entire communities in New York City is at the roots of the story of one of the most genuine ecopoetic voices in world sculpture.

The artist deeply admired by poets like E. E. Cummings, Ezra Pound, Charles Olson, Richard Howard and Yannis Ritsos, among others, the persistent friend of trees and plants, realized with his work an absolute intimacy between subject, matter, imagination and time fulfilled by care.

Mostly self-educated and most erudite, Lekakis had delved into Aristotelian principles, Cycladic forms and archaic sculpture, into Pre-Columbian art and Mexican crafts, indigenous totemism and universal symbolism, poetry, pre-modern rituals, Eastern philosophies, Byzantine murals, mathematics and physics, Greek folk song, dance, Brancusi’s wooden works and altars, mysticism and ancient geometry, abstract expressionism, Greek architecture, surrealist biomorphism, military camouflage techniques and model construction, the art of adorning and “ordering” with flowers, and cosmology.

All of them are encounters that manifested his Foucauldian kind of curiosity, a concern for what exists and what could exist.

Lekakis was known for probing things (trees, poems, drawings), nudging and cajoling them, returning to them through the years in order to understand the cosmos: the flowers and trees he grew, the ferns he preserved, the branches he bended, the roots he studied, the wood, lines, shapes, language, poetry he cared for.

His mode of chiseling away at materials of any kind is not a means to get things right, proper, minimal, or abstract. It feels more like a quest for a precision that honors what is at hand; a therapeutic, gradual touch with layers of proximity, unveiling.

It comes across not as a style but as a vernacular, a jargon even that requests the viewer’s invested attention, effort, play, reciprocity. It is a way to place oneself amidst things instead of away, at the observer’s point.

His work is antiheroic, unmonumental, untimely in that it chose wood and thus demythologized his own classical Greek heritage in its perception by the West; linking forms like the column or the sphere with the more-than-human world, its seasonality, slow time and atmospheres, this work differentiates itself within an epoch that favored grand gestures, the promise of infinity, the readymade.

It honors the kind of craftsmanship mostly associated with everyday labor, primitive artifacts and outsiders’ creations, and reveals a deep respect for an economy of means.

Elusive in its idiorrhythmic affinities to abstraction, constructivism and surrealism, it is mostly imbued with a kind of animism that relates to a symanimagenic process of creation and actively denies the objectification, divisions and classifications that colonial modernity enforced upon species and cultures via its evolutionary, anthropocentric and eventually catastrophic worldview.

In drawing, writing, painting and sculpture, Lekakis weaved his very own variegated ecosystem by engaging in an anti-hegemonic mimesis of other, natural and cultural, systems; mixtures and diffractions, formless formations and inherent structures, osmosis, cross-pollination, the biological and the astral, the micro and the macro; in other words, attunement to a non-geotropic, non-monocultural cosmos.

The artist considered creation to be not the result of will, but of “a process of sensitization and preparation,” an open talk with matter on the road to realizing “its full potential.” Mediation, long-term engagement, informed intuition, the honing of skill to the point where it becomes natural, magic; the reconciliation of man with the world.

Yannoulis Chalepas may come to mind as the artist of quite the keen rapport with flawed materiality, the tactility of textures, liminality, precision, incompleteness. Their works, different though they may be, come across as accomplices with the untamed life of the more-than-human world, sharing as they are not its forms but mostly its breath, its hauntings and atmospheres.

Lekakis’s woodwork does not romanticize nature. It captures growth as a kind of multiplanar soaring, dancing, crawling, swelling, falling; upwards, but also downwards and waywards. Pedestals are important as much as what is placed on them. See his most daring work “Apotheosis” (1964–1972), where the entangled roots of a trinity of oaks reach to the skies as the antennae they really are, both fragile and menacing. The work seems to come as a response to an exigency to which the artist cannot fail to respond.

Think of nature’s queer performativity, or the question asked provocatively by Karen Barad: “What if we were to understand culture as something that nature does?”

It feels like Lekakis—who spent his time watching trees grow and morph before taking their wood; who delayed cutting, rasping, etching, to avoid arbitrariness visàvis nature’s agency; who wrote about plants, birds and grass from the guts of a world metropolis—practiced way ahead the radical knowledge that philosopher Emanuele Coccia recently shared about the life of plants and the metaphysics of mixture: “the genesis of forms achieves in plants an integrity inaccessible to any other living being…Plant life is nothing but the cosmic alembic of universal metamorphosis…The plant is nothing if not a transducer, one that transforms the biological fact of the living being into an aesthetic problem and makes of these problems a question of life and death.”

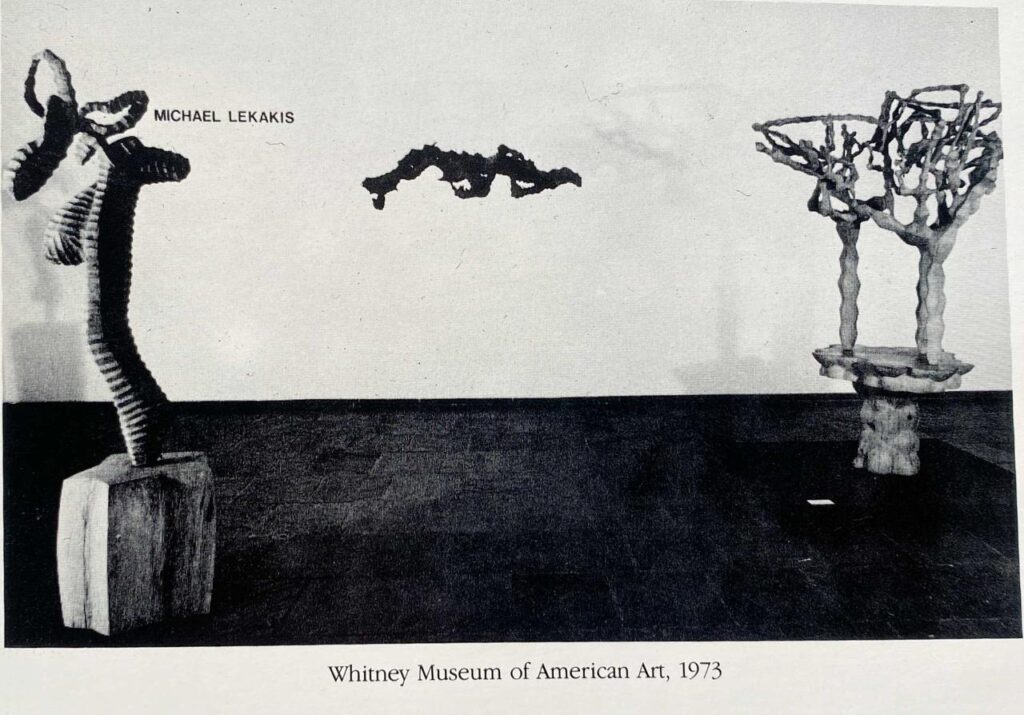

Intensely private, notoriously indifferent to fame and glory, modest and reflective, largely unable to part with his works, bearing an aversion to art market commitments and commercial politics, victim of the national heritage rubric (“Greek-American artist”), Lekakis reached a peak of recognition abroad via the admiration of mostly poets and thinkers, and was included in publications and articles of art criticism during the ’50s and ’60s as well as at museum shows (the Whitney, Guggenheim, MoMA, the Dayton Art Institute, et.al).

He was then forgotten or misread by the existing art discourse. Critic Bernard Harper Friedman (1926–2011) attempted a contextual evaluation of his work in the catalogue for the “retrospective exhibition” organized by Kouros Gallery in New York, in 1987. Humanist philosopher and university professor Joseph Margolis (1924–2021) wrote via a long engagement with the artist’s work, and his 1975 text “Michael Lekakis and the ‘Heuristics’ of Creation” is the most quoted. Despoina Spanos Ikaris dedicated a long documentation of his art in the 1976 issue of “The Charioteer: An Annual Review of Modern Greek Culture”. Things leave much to be desired in Greece; limited critical mentions and only two exhibitions organized at the National Gallery (1980 & 1988) in response to, and in memory of, Lekakis’s generous gift of 7 sculptures and 22 drawings “to the Greek people.”

[Image on the left: Drawings at Lekakis’s studio. Dance Sequence 1950 on the left and Cosmic Echoes on the right.]

[Image on the right: Lekakis’s studio in the US]

Researching for years Michael Lekakis’s art, both in Greece and in the States (in his studio in Long Island and gallery in NYC), and writing about it, I often thought of how pertinent, urgent even, a returning to its many neglected aspects would be in the present, under the light of different, transdisciplinary modalities of thought: a return to its very own strain of metaphysics and deviant modernism, to its environmental acuteness, haptic visuality, orgasmic performativity; to its reverence for anticipation and suspension, for (in)visibility, (de)camouflaging. A return to Lekakis’s very own sense of degrowth.

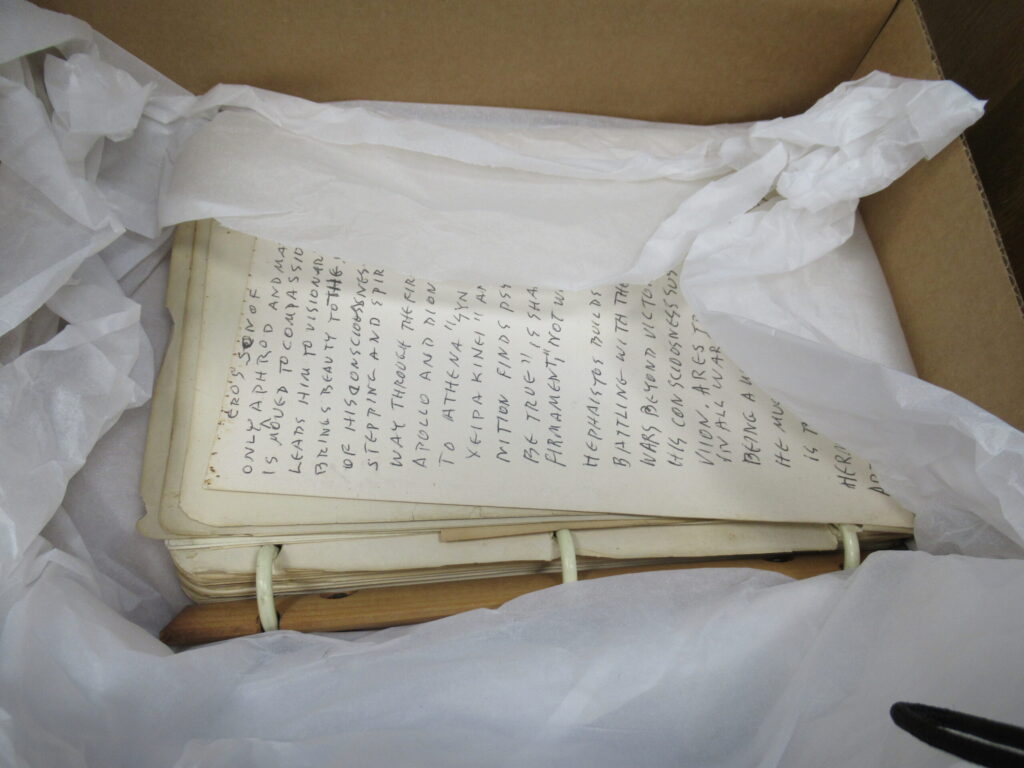

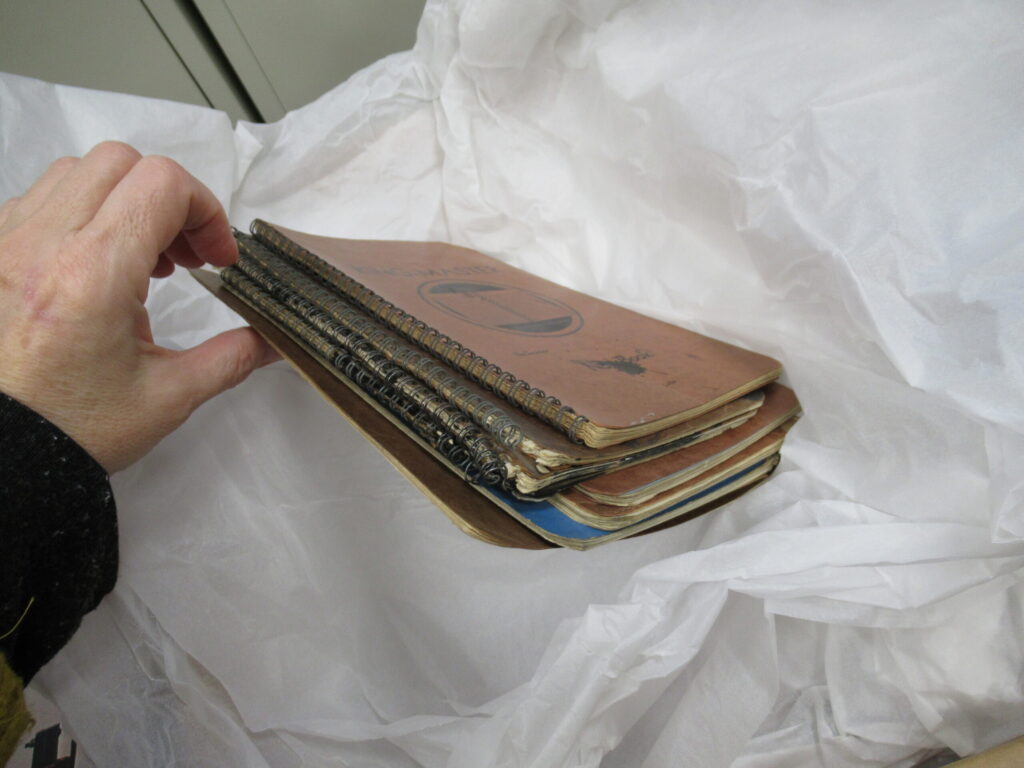

Coming upon the treasure of his hitherto unpublished notebooks in the ACG Art Collection—next to many paintings, drawings, sculptures and his very own toolbox—was an encounter that sharpened that sense of urgency.

For Lekakis, love is the cosmic accelerator, something that he had written about in his self-published poetry collection “Eros Psyche” of 1973. Composed in Greek, these poems were translated in English by the author himself and are quite enriched and complicated through his notes.

The importance of these notebooks lies in the way they illuminate the artist’s worldview, in their being his lifelong companions, in how they carry and convey mood, substance, touch, pulse: an unassuming, stretched out in time peeling off of meanings; a situated process of articulating and lacing together, of collective storytelling much like the ceremonial making of roping and wreaths at Lekakis’s family shop. Words in rhythmic succession, in Greek and English, in blooming clusters; verses reworked or erased, uneasy like a swarm, connected like atoms, choreographed through breathing intervals; meanings carved out of cosmic visions and lack thereof, truths hoaxed into manifestation; writings in disregard of proper dictation, in capital letters, in search of the prima materia, in a semi-automatic reverie, in lament of ecocide, in memory of the future, in hope for the stars, in register of Karen Barad’s spacetimemattering, in celebration of a cutting together-apart that this master wood-carver learned from nature.

[All images that follow are pages from Lekakis’ notebooks, part of The American College of Greece Art Collection, a gift from Takis Efstathiou]

Nikos Velmos (1890–1930)

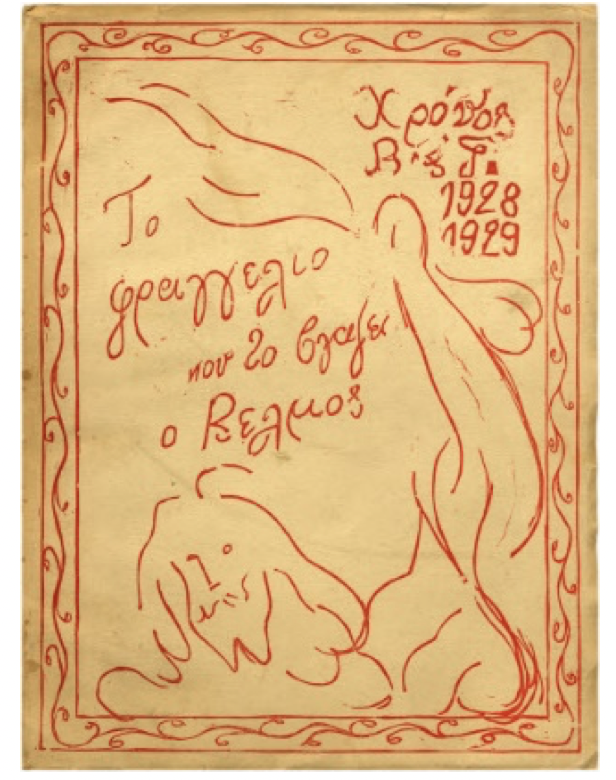

One of the most fascinating bodies of materials in the ACG Art Collection is a donation by Takis Efstathiou that involves works and testimonies about Nikos Velmos.

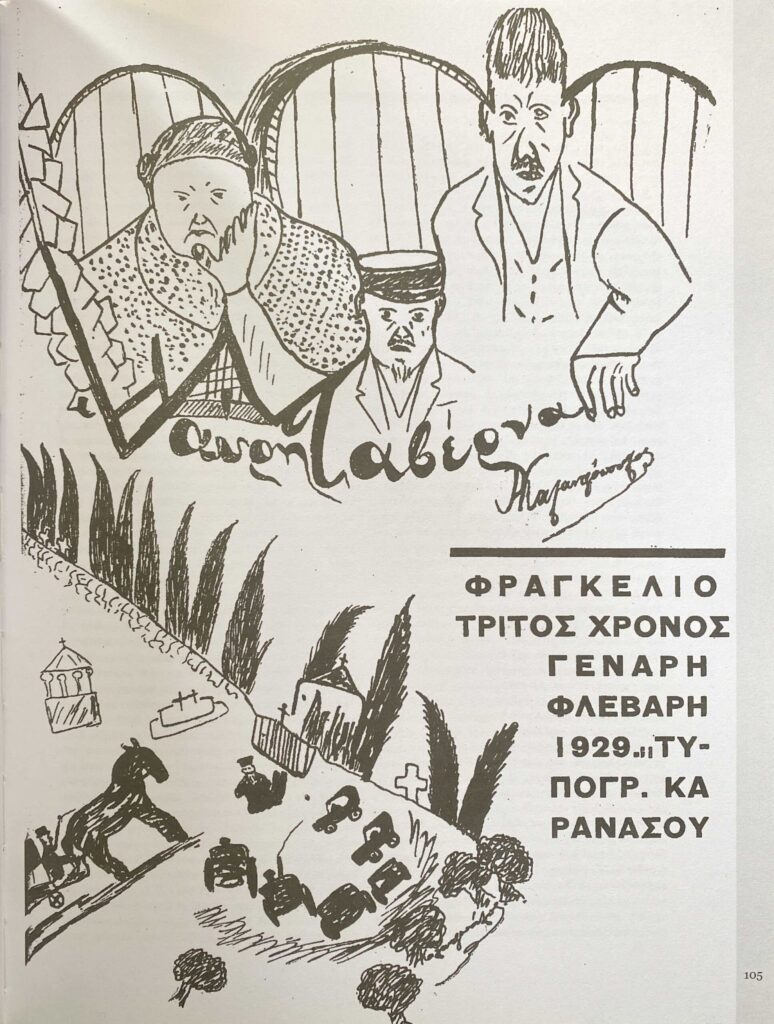

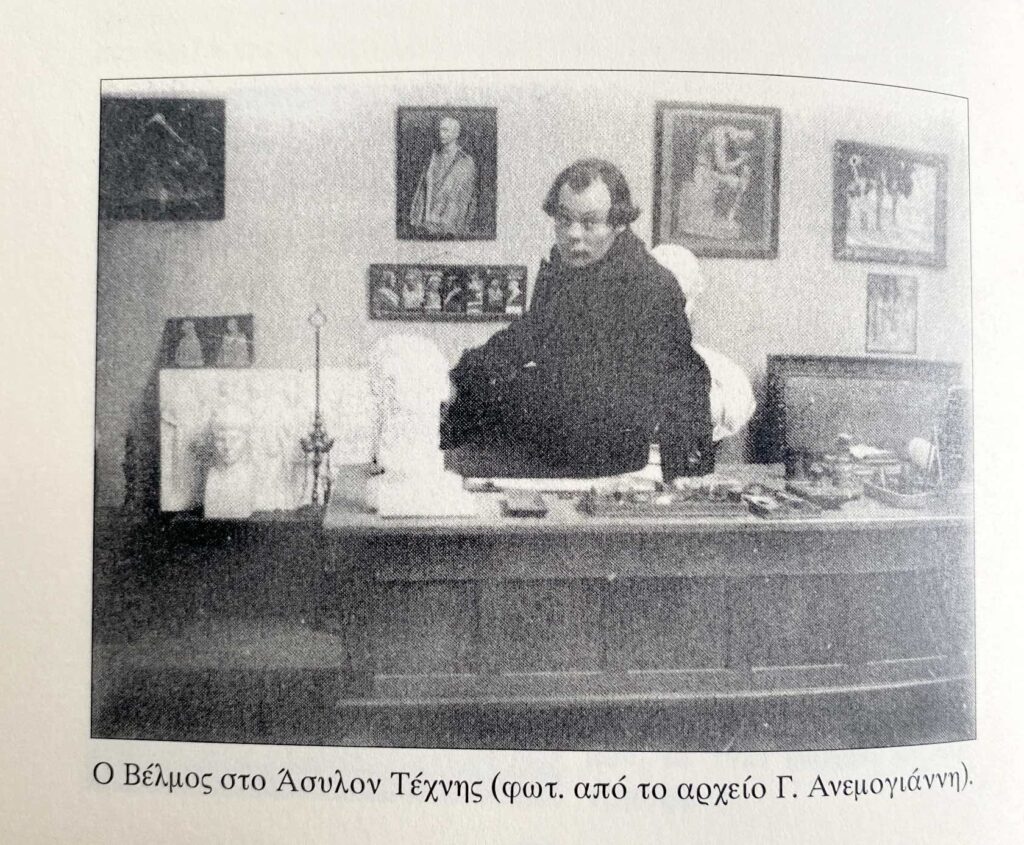

Actor, theatre director and manager, poet, self-taught painter, writer, passionate art critic, dedicated wanderer, transgressor of criminal law, bohemian, homosexual, charismatic speaker, essayist, caretaker of forgotten graves at the First Cemetery of Athens, curator of innovative exhibitions, fierce polemicist of elitism, drug addict, publisher of the legendary journal “Frangelio” (The Scourge) and the related art supplements “Fylla Technis” (Art Papers), founder of the non-commercial art space “Asylon Technis” (Art Asylum), Velmos was an exceptional personality with a strong political stance, social participation and avant-garde practice in favor of those who were marginalized and ignored in Greece of the first decades of the 20th century.

Velmos (a pseudonym that echoed the name of his hero William Shakespeare) was born at 21 Nikodimou Street in Plaka, the fifth child of shoemaker Michalis Vogiatzakis, with roots from Crete. Together with his four sisters and one brother, Velmos spent his childhood years visiting the family’s neighbor, the witty, irreverent and impoverished novelist Emmanuel Rhoides. His life choices remained imbued with a strongly unconventional, particularly scalding, anti-militarist, combative spirit that defended the weak and voiceless and attacked every kind of establishment of that time, including the church, the intelligentsia and the political authorities. A mixture of socialist and anarchist ideas, Velmos’s manifestos circulated in word and deed, and aroused both sympathy and indignation while defending the absolute identification of poetry with life.

A friend of artists like Kontoglou, Papaloukas, Chalepas, Rengos, Tsarouchis, of known as well as disregarded poets, writers, actors, also friend with the poor devils, low-class workers and dissidents of every kind, Velmos roamed the streets, coffee shops, taverns, meeting places of Athens, staged plays and organized art shows, studied within the undercommons and their antagonisms, defended and nurtured the relations that grow in social life, in intimacy, in intellectual and bodily copresence.

All things considered and historical differences put aside, one may discover in Velmos’s ever growing, celebratory host of defiant interactions and visionary initiatives, in his engagement with publications (a form of social space by themselves), in his own kind of Athenian dérive, his sort of errantry-as-refusal, in his tender drawings and heated writings, in the con/temporal extimacy of his work, a genuine, bottom-up move towards the kind of social pedagogy and the kind of “lively arts” that the world enjoyed during the ’60s and ’70s, or the kind pursued via contemporary quests regarding social, gender and environmental justice.

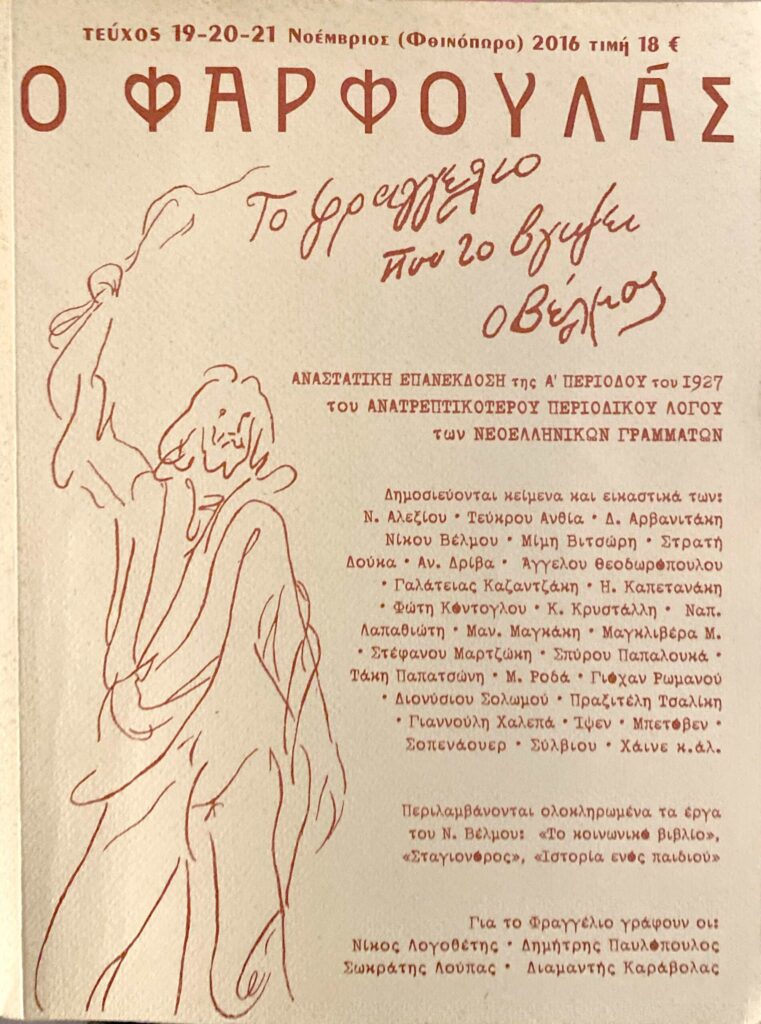

The exhibition “outraged by pleasure” (Nobel space, Chalandri, Sept.–Nov. 2023) brought together works (kindly lent by the Frances Rich School of Fine and Performing Arts at Deree) and testimonies by as many as possible of those who have engaged with the work and life of Velmos in the past: Diamantis Karavolas and his Farfoulas Publishing, the late Nikos Logothetis (see his 2016 book, “Nikos Velmos (1890–1930): The Son of Loss”), art historians Kimon Theodorou (see his 2021 book, “Velmos and the Exhibitions at the Art Asylum”), Venia Pastaka and Galini Notti.

Most importantly that exhibition project summoned Velmos’s spirit of rebellious conviviality, solidarity and social responsibility and, in a trans-agential move, hosted it within an oddkin of other creative spirits, collectives and initiatives in an ensemble of contemporaries (in Giorgio Agamben’s use of the term).

There is still a lot to be researched and appreciated about Nikos Velmos, the circumstances and particulars of his activities, their web of relations and implications that, both at his time and largely still, were/are labelled simplistic or naïve.

What this notebook salutes among other things is a creative who practiced autonomy and at the same time denied individualism, who offered a countercultural paradigm that could join the more obscured ones among those threaded by Gregory Sholette in his long research on the precarious promise of cultural resistance and the “dark matter” of creative life.

[All images that follow are from Velmos’ works, part of The American College of Greece Art Collection, a gift from Takis Efstathiou. Pages that appear as scans come from Farfoulas Publications]

At the current moment, when the promise of social media has been stifled into a horrific flattening of effect and affect; at the tipping point of neoliberal democracies’ massive failure; at the disheartening reality of institutional art’s enthusiastic engagement with generative AI and its selective blindness toward the chasm of access that so opens; at the thrust of algorithmic delirium and data mining; at the retreat of progressive politics and the rise of authoritarian voices; at the brink of global meltdown—we could possibly bring in our untraceable notebooks and radical ceremonies. In recognition, in occupation, in crossing through the current moment.

In the sustainable destruction of the suns that must be eclipsed and in alliance with the fireflies that need to be empowered.

)

)